The Age Lie: What Wearables Get Wrong About Our Bodies — And What That Says About the Future of Health

Introduction: When Two Bodies Tell Two Different Stories

Recently, I attempted to reconcile two different sets of numbers that estimated the biological age of my cardiovascular system.

On one side were my clinical results. I had undergone a comprehensive cardiovascular workup that went far beyond standard cholesterol checks. This included detailed anatomical and functional testing: a VO2 Max test, an aortic pressure pulse test (PVR) to measure arterial stiffness, a 12-lead EKG, and a 3D echocardiogram to visualize the heart structure directly.

We went even deeper with a Multi-Proteomic Biomarkers Test—a prognostic blood test that analyzes unstable proteins to predict the 1-year risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), such as a heart attack or stroke. These are tests that any cardiologist or functional medicine physician would recognize as the "ground truth" of physiological status.

When combined with genetic testing from previous visits, the picture was stark. Despite my external metrics—my strength, exercise routine, and BMI suggesting I was fit—the deep clinical data painted a more complex, granular reality.

On the other side was the picture painted by my wearable devices.

To be transparent, I use devices from arguably the most reliable players in the space: Whoop, Oura, and Polar. Like many people in the health and performance space, I have grown accustomed to checking my “readiness” scores, sleep stages, HRV trends, and my so‑called “biological age”.

Here lies the conflict. When I tried to map my clinical reality onto these devices, I didn't just find a slight deviation; I found fundamental incoherence.

One device characterized my cardiovascular function as consistent with a markedly younger biological age than my chronological baseline. Another estimated a cardiovascular age approximately six years younger. In other words: depending on which screen I looked at, I was either a physiological anomaly or simply "doing okay."

The Validation Experiment: A Methodological Mess

To dig deeper, I decided to run a controlled comparison. I incorporated a Polar chest-strap system to capture continuous, activity-adjusted cardiovascular performance metrics—widely considered the gold standard for non-invasive heart rate monitoring.

During standardized cardiovascular stress and recovery assessments, the results were telling. Neither Oura nor Whoop demonstrated calibration concordance with the Polar-derived measurements. Their data drifted, painting a picture of my physiology that didn't match the electrical reality of my heart.

In contrast, the Polar outputs aligned closely with Cardiex-based assessments obtained in a supervised cardiology setting.

The conclusion was unavoidable: the consumer wearables were operating on non-equivalent constructs. They were limited by proprietary weighting and "black box" feature selection that I could not see or validate. They weren't measuring my heart so much as they were modeling it—and the model was flawed.

This article is not an attack on wearables. I use them daily and recommend them often. But they are not, and should not pretend to be, replacements for proper medical evaluation or diagnostics.

Instead, I want to explore a more honest question: what exactly are wearables measuring, what are they missing, and what would it take for these tools—and the regulators overseeing them—to become truly trustworthy companions in our pursuit of long‑term health?

What Labs Actually Reveal: The Depth of Biology

To understand where wearables help and where they fall short, we must contrast them with the current gold standard: clinical testing.

When a cardiologist evaluates risk, they do not rely on surface-level proxies. They look at a mosaic of data points that tell a story about structural and functional integrity. The specific tests I underwent highlight this difference in depth:

Structural Integrity (3D Echo & PVR): These tests visualize the heart muscle itself and measure the stiffness of the arterial walls. They aren't guessing about blood flow based on light reflection; they are observing the physical "plumbing" directly. PVR can detect hardening of the arteries long before a heart attack occurs.

Proteomics & Genetics: A Multi-Proteomic test doesn't just measure current stress; it analyzes unstable proteins that signal future instability. It provides a probability score for catastrophic events based on molecular reality—something no wrist sensor can detect.

ApoB and LDL‑C: These markers count the actual number of plaque-building particles penetrating your arterial walls.

Inflammatory markers (hs‑CRP): This reveals if your system is “on fire” with inflammation, a critical driver of arterial disease.

The key point is straightforward: Labs measure biology directly. They look at molecules, structures, and pressure gradients. None of these values exist as a single, magical “health score.” They are interpreted in the context of your genetics and history.

What Wearables Measure: The Surface Signals

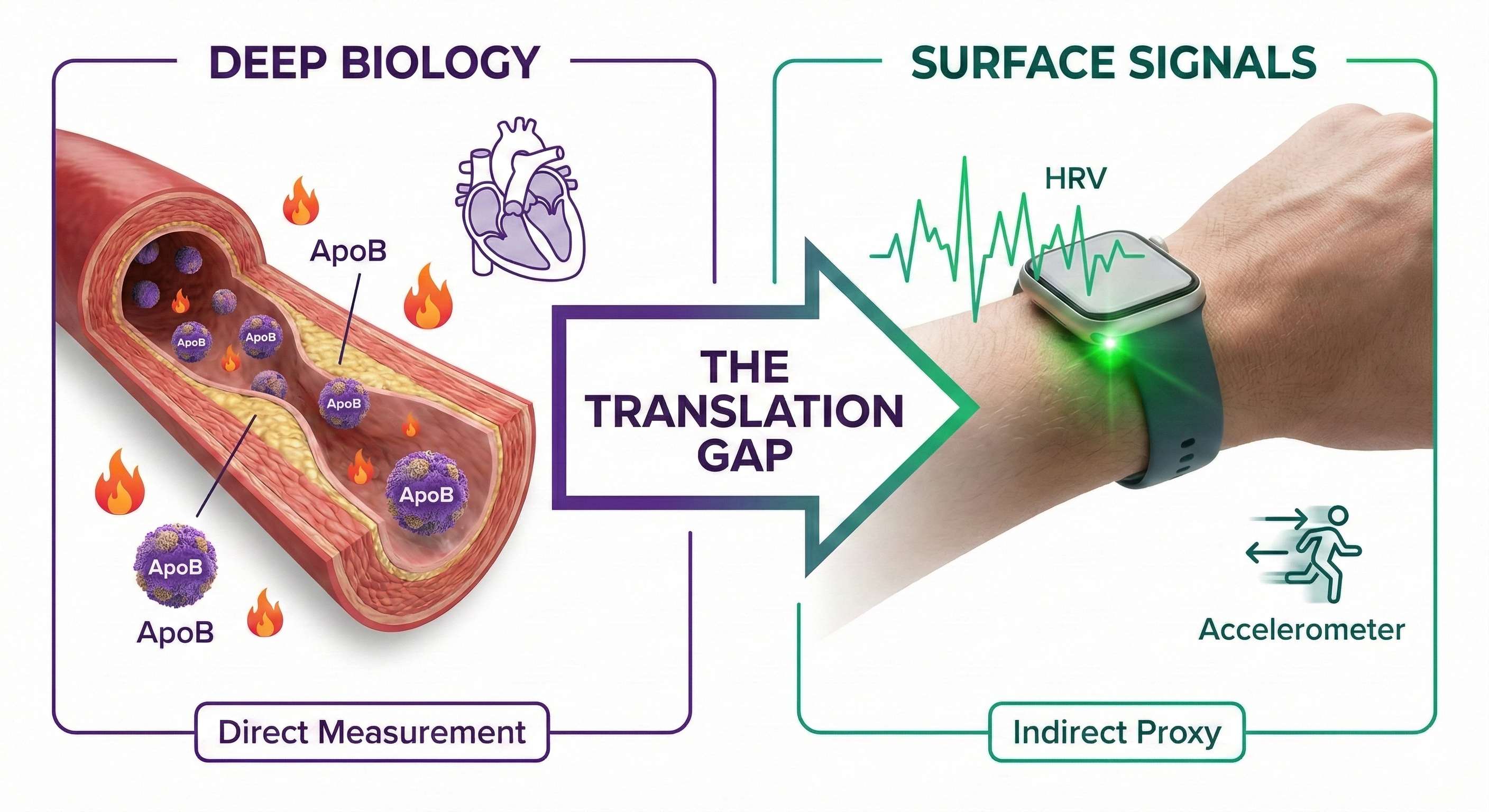

Consumer wearables operate in a fundamentally different world. They do not have access to your blood, your vessel walls, or your proteins. Instead, they rely on proxies—surface signals that are easier to capture but much harder to interpret.

Heart Rate Variability (HRV): A useful metric for nervous system balance, but heavily influenced by hydration, stress, and even how you slept the night before.

Sleep Staging: Wearables estimate sleep stages using movement (accelerometers) and pulse (PPG). Unlike a clinical sleep lab that measures brain waves, wearables are making a "best guess" based on motion and heart rate.

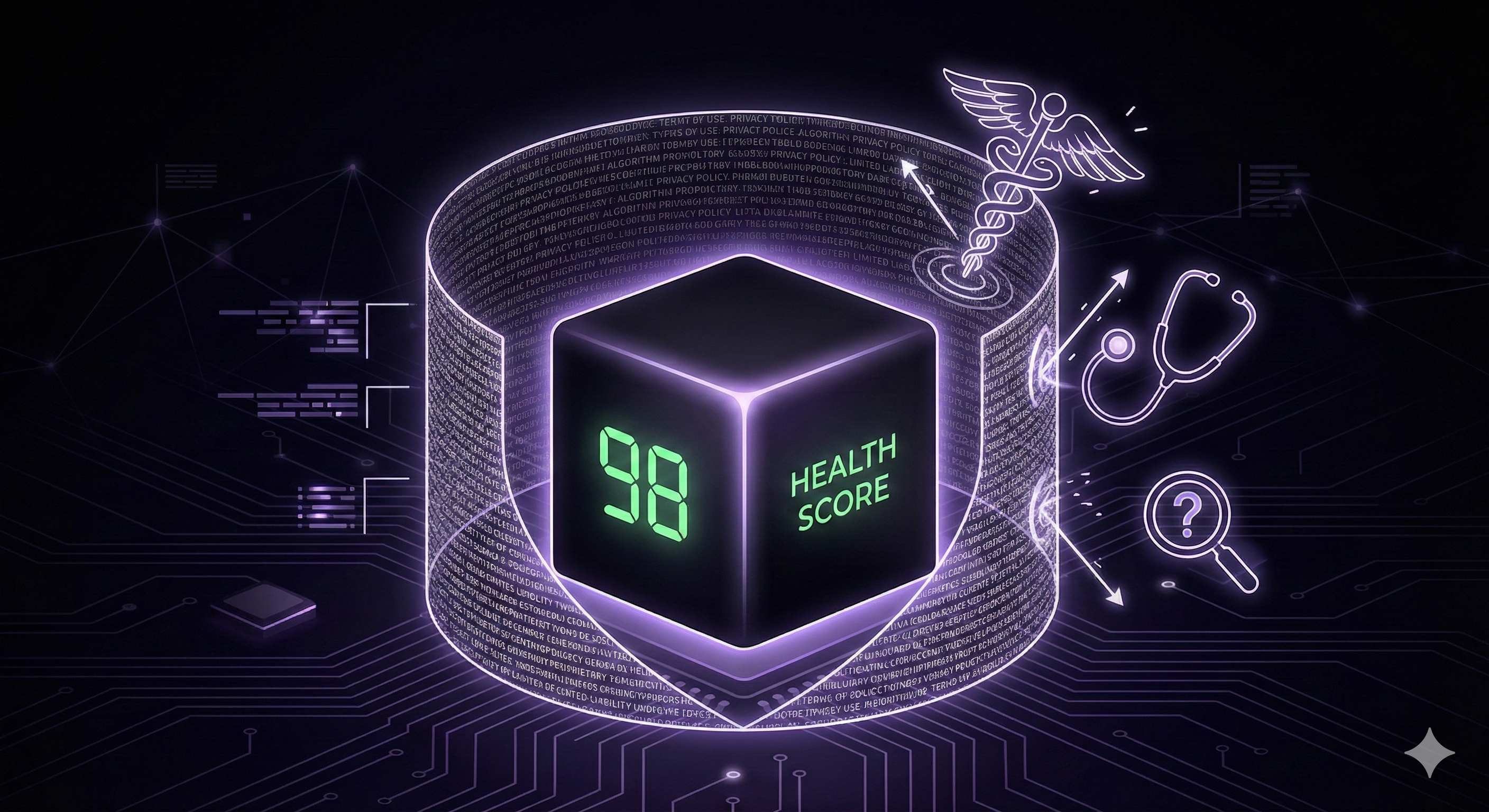

Biological Age Scores: These are the most seductive numbers. They claim to summarize your total health, yet they are generated using proprietary formulas that mostly combine HRV, resting heart rate, and activity levels.

In short, wearables measure signals, while labs measure substance. Algorithms try to translate those signals into meaningful health insights or a digital representation of homeostasis (balance), but that translation layer is often where the "truth" gets lost.

Why Wearables Get It Wrong

If wearables are not useless, but also not fully reliable, where do they go wrong?

1. Oversimplification of Physiology

Human physiology is not linear. A decline in HRV might be a sign of illness, or it might just mean you had a hard workout yesterday. Algorithms often treat complex adaptive systems as if they obey simple, static rules.

2. Missing Biochemical Data

No matter how sophisticated a wearable’s sensor is, it cannot see your proteomics, your ApoB, or your insulin resistance. It cannot see plaque accumulating in an artery. Yet, it will still assign you a "Health Score" or "Age" that implies everything is fine.

3. Context Ignorance

Wearables are blind to context. They don't know if you are stressed because you are sick, or because you are caring for a dying parent. To an algorithm, stress is just data; to a human, the cause of the stress changes the diagnosis entirely. As such, wearables have adopted "behavior nudging" techniques via journaling in an attempt to collect qualitative information, but this relies heavily on user compliance.

How I Use My Wearables Now

Until the future arrives, here is my rule of thumb for interpreting the numbers on your wrist:

Use them for Trends: Are you deviating from your baseline over 7+ days?

Use them for Behavior Modification: Understanding how alcohol or late meals affect your sleep.

Use them for Acute Shifts:A sudden spike in Resting Heart Rate or Respiratory Rate can be a "Check Engine" light for illness.

Use them for Stress: Respiratory Rate and HRV are reliable for providing insights on your body’s ability to manage stress.

But be skeptical of:

"Biological Age" numbers: Without clinical testing, blood work, and anatomical data, these are just marketing.

Cardiovascular risk estimates:Your watch cannot see the protein markers or arterial stiffness that define true risk.

The Regulatory Void: Why "Terms of Use" Isn't Enough

We are currently in a "Wild West" phase of health technology. While the gap between clinical truth and wearable scores is technological, it is also regulatory.

Currently, the collaboration between the tech industry—which prioritizes speed and user engagement—and the health industry—which prioritizes safety and accuracy—is fractured. Regulatory bodies like the FDA have been arguably too lax with consumer devices, allowing them to market "Health Scores" and "Readiness" metrics that mimic medical advice without the burden of medical validation.

Tech companies currently rely on a "get out of jail free" card: the Terms of Use.

Buried in the fine print that few users read is the disclaimer that the device is "not intended for medical use." This allows companies to gamify your health data while absolving themselves of responsibility when their "Age Score" contradicts a cardiac MRI. It places the entire burden on the user to discern what is entertainment and what is medical reality.

This lack of intervention allows for a marketplace where "coherence" is nonexistent. One device says you are 25; another says you are 45. Without a standardized framework for how these algorithms are validated, consumers are left navigating a hall of mirrors.

For the future of health to work, we need more than just better algorithms; we need:

1. Integrated Models: Where clinical labs (the ground truth) feed into wearable algorithms to calibrate them.

2. Stricter Validation: We need regulatory intervention to drive standards. If a device claims to measure "Cardiovascular Age," that claim should be validated against clinical standards, not just internal company data.

3. Transparency: Companies must stop treating their health scoring algorithms as black boxes.

Bridging the Gap: What the Future of Health Should Look Like

This desire for a single number is deeply human. We want a credit score for our finances and a star rating for our restaurants. It is natural to want a “health score” that sums up our biological reality. But biology is not a bank account; it is a landscape.

If we accept that labs measure the landscape and wearables measure the weather, the obvious next question is: can we bring these worlds together?

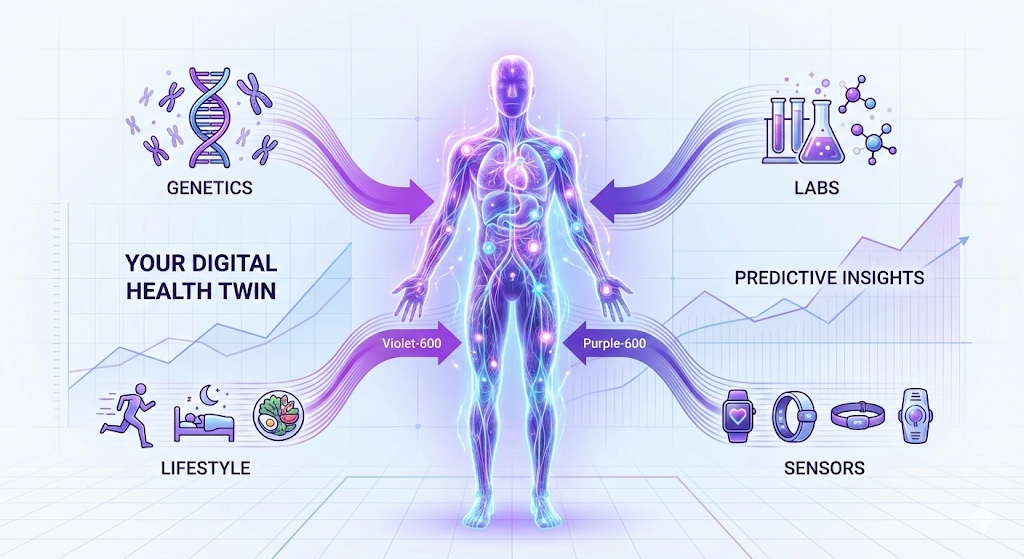

1. Integrated Models: Labs + Sensors

Imagine an annual or semi‑annual cardiovascular and metabolic panel that does not just live in a PDF on a patient portal, but actually feeds into your wearable’s algorithm.

Your ApoB, LDL‑C, HbA1c, and other key markers could act as “ground truth” for the model. Instead of guessing your biological age from HRV and sleep, the device would reconcile its estimates with real biochemical data. The result would not be a perfect model—no model is—but it would be anchored in the kind of information we already know predicts long‑term risk.

2. Context‑Aware Intelligence

This is where modern AI can play a transformative role. Instead of passively showing you a readiness score, a future‑generation system could integrate your biometric data with contextual inputs: travel schedules, training logs, and self‑reported stress.

Rather than simply stating, “Your HRV is down,” the system could say:

“Your HRV is down and your resting heart rate is up compared to your 30‑day baseline. You also slept 4 hours last night and reported two alcoholic drinks. This pattern likely reflects short‑term lifestyle factors rather than a decline in overall health.”

3. Personalized Health Twins

Finally, we can imagine a future in which each of us has a personalized “health twin”—a dynamic model that integrates genetic risk, metabolic labs, lifestyle factors, and continuous biometrics.

This model would update as new data streams in. We are not there yet, and there are serious privacy and equity questions to address along the way. But this is the kind of integration that would justify the strong claims already being made on marketing pages.

Closing Message: The Truth Behind the Numbers

So, what do we make of situations like mine?

Those two sets of numbers still show up in my life: one from my blood, one from my wrist. I no longer ask which one is “right.” I ask what their disagreement is trying to tell me.

Wearable-derived metrics provide clinically useful insights into select physiological domains, but they offer an incomplete representation of biological aging. These measures do not capture epigenetic modulation, environmental exposures, or adaptive biological processes that substantially influence aging-related risk and resilience.

Real health will come from merging biochemical reality with continuous biometric intelligence. Until that integration happens—and until standards are enforced—I will continue to use my wearables for trends, but I will trust my life to the labs.

When the numbers disagree, I treat the discrepancy as a prompt to ask better questions, seek deeper understanding, and remember that no single app can fully summarize the complexity of being human.